e-SPAN Newsletter v037: AI and Building Information Modeling in Architectural Practice

Dear School of Architecture Community,

Our Spring semester began with new challenges brought on by the incoming federal administration. In quick succession, executive orders pertaining to research funding and Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) created much confusion and consternation. If these proposals become abiding, they will have a profound effect on academia and its mission. We, like other universities, are navigating this carefully, and it is too early to tell what the real effects will be. Suffice it to say that we are committed to our values of freedom of thought and speech and providing the best education for all of our students.

In this issue of e-SPAN, we continue to shed light on the growing role of AI tools in architecture. In interviews with PhD student Yael Netser (PhD-AECM ’27) and alumnus Jared Friedman (B.Arch ’10), they discuss how AI is being integrated into Building Information Modeling (BIM). They highlight its role in organizing and collating data that can facilitate the quantitative aspects of the design process. This can have profound effects on a project's sustainability assessments and costs, which could in turn lead to more efficient designs. The interviews also speak to the limited amount of available building information on which to train AI tools. This limitation will need to be addressed for these tools to be truly effective. Research funding for AI will likely be a priority for this federal administration; whether it takes place in academic labs or through private industry is an open question.

This year we are celebrating the 10th anniversary of the NOMA chapter in Pittsburgh. Faculty member William J. Bates and former faculty Gerrod Winston are some of the founding members of the chapter, which has grown and had a huge impact on the Pittsburgh professional community. I was proud to see just how many of our alumni, from UDream and other programs, have made this chapter a success. Diversity is our strength, and the Design in Color gala celebrated the success that our community has achieved in such a short time. Our faculty, alumni and students were recognized through the organization’s annual awards program: Professor Erica Cochran Hameen, PhD, received the inaugural William J. Bates Legacy Award for Social Impact; and Starr Wasler (B.Arch ’26) and Shayla Thomas (M.Arch ’24) received the 2023-24 NOMAS Emerging Leader Award. We extend our congratulations to them.

Finally, we also recently celebrated our first cycle of the PJ Dick Innovation Fund Faculty Grants Program. The PJ Dick Trumbull Lindy Group established an Innovation Fund to support the pedagogical mission of the School. These grants support faculty research projects and innovative teaching and course development. We were honored to have co-CEOs Timothy O’Brien and Jake Ploeger join us for the celebration. As the research climate shifts at the federal level, we can’t thank PJ Dick enough for providing us this support to our educational mission. You can see some pictures of the work below. Stay tuned for the next issue of e-SPAN to learn more. The next cycle of awardees has been announced, and we look forward to celebrating their work next year.

Omar Khan

Head of School

Professor & Head

Yael Netser (PhD-AECM ’27) doesn’t imagine that artificial intelligence will replace human architects any time soon.

Netser, a PhD candidate in Carnegie Mellon Architecture’s Architecture–Engineering–Construction Management (AECM) program, encourages architects to embrace their essential identity as problem-solvers to most confidently manage, embrace and deploy AI tools in their design work.

Like many of her colleagues, she has found AI tools to be helpful assistants in tasks like rendering, aggregation of information, and rapid parametric design iteration. But she adds a bit of nuance to the inclusion of AI in the architectural design process. AI, she says, is best suited mostly for undertaking quantitative tasks, while architects remain responsible for the qualitative whole: seeing the big picture, addressing complexity and balancing multiple values for a built environment that makes sense.

As a licensed architect and Building Information Modeling (BIM) consultant, Netser has long understood the value of the “human in the loop.” Even an information-driven design that successfully addresses all quantitative parameters might make little sense aesthetically, experientially or ethically. A seasoned designer understands this, knows that generative design processes are neither infallible nor sufficient, and sorts through algorithmically generated design solutions to find those best suited to the ways humans live and work. The advent of BIM didn’t herald the end of the human architect, and neither does the rise of AI.

There are major differences, though, between the ways BIM changed the building industry and the changes Netser sees as necessary responses to the current AI landscape.

Before the advent of BIM, says Netser, designers were accustomed to describing their buildings in two dimensions — plans, sections, lines. Now, with BIM tools, they had to describe buildings in three dimensions — in terms of models or elements. “The primary obstacle to designing with BIM was and continues to be the interface,” she says, “because BIM programs tend to be very difficult to learn and operate, with a long learning curve.”

Current AI, she continues, “is exactly the opposite: AI applications are extremely friendly to the user, for better or worse. When the user needs only to enter a prompt and a design is auto-generated, all processes are hidden behind the scenes, and the user can’t control them.”

(Editor’s note: The AI tool used to transcribe this interview succinctly, and perhaps cheekily, summarized this point thus: “The conversation touches on the differences between the adoption of BIM and AI, with AI being more user-friendly but potentially less controllable.” Netser, one of two humans in this interview loop, would again add nuance: AI and BIM aren’t mutually exclusive competitors. AI, used well, leverages the information captured by BIM.)

The user-friendliness of AI tools, says Netser, has one counterintuitive result: designers will need to learn or relearn ways of designing without tools that slow the process. “We are so used to having tools that make designing harder: you have to translate the design in your mind using your hands and a pencil, which cannot easily describe complex geometries; or you use a computer program that can express complexity but requires numerous mechanical steps for a single artistic action.”

The relative effortlessness of AI-powered design, in contrast, requires new skills and ways of thinking.

One design mode Netser encourages architects to lean into: language. Since many of the most sophisticated generative-design tools are large language models trained on huge bodies of text, the quality of their output depends heavily on the linguistic precision of the user’s input. As Netser says, “we’re very used to using our hands to draw or to model; we need to learn a new way of thinking and designing verbally.”

Netser insists that architects can embrace AI and its new demands without fear. Architects, she says, are fundamentally problem solvers, always working to maintain a complicated balance of numerous values, parameters and stakeholders. They are accustomed to being accountable, responsible for human safety and thriving in the built environment.

That, Netser says, is not changing. “Different stakeholders have different interests in the design of a building, and an architect is ethically responsible for the good of the public and the good of the users. So even as AI helps maximize spaces’ efficiency or profitability, we still need the human, responsible architect who will take care of spaces’ quality, social sustainability and equity. It’s not that AI won’t be able to consider these things; I think it will. But we as architects are responsible for ensuring that it does.”

Netser brings this nuance — new ways of design thinking, intersections with generative design, and an insistence on human-centeredness — to the class she’s teaching next fall, “BIM for Architects: Leveraging Revit Parametric Design to Empower Innovative Architectural Design Practice”. The course focuses on novel technological tools at the intersection of BIM and AI, helping architects achieve value-based design. For those unable to take her course in the fall, check out her Autodesk University class, "Ethics in Computational Design: Infusing Equity into AI and Generative Design for Building Design Processes."

According to Jared Friedman (B.Arch ’10), artificial intelligence is successfully “unlocking some of the latent value of BIM datasets,” and in turn, AI is improving how designers work with BIM.

Since the advent of Building Information Modeling (BIM), design firms have collected huge amounts of metadata. “But at the end of the job,” says Friedman, “that data just dies.” There are multiple, cascading reasons for this: “designers’ BIM data often lacks the information needed by contractors and operations teams downstream, so there’s little demand or incentive for sharing models. And even when models are shared, clients rarely have the knowledge or software to effectively use them.”

Now, though, those datasets can be used to train AI models that can, in turn, extend their usefulness in improving building efficiency and sustainability.

Training AI on BIM: Early Projects

Friedman is a Computational Product Manager at Walter P Moore, where he works on a computational design team alongside software developers and AI specialists. Together, they create digital tools and workflows that help structural engineers deliver large, complex buildings. Recently, this work includes leveraging BIM datasets the firm has built through years of work to create AI-driven tools that quickly solve old, tedious design problems.

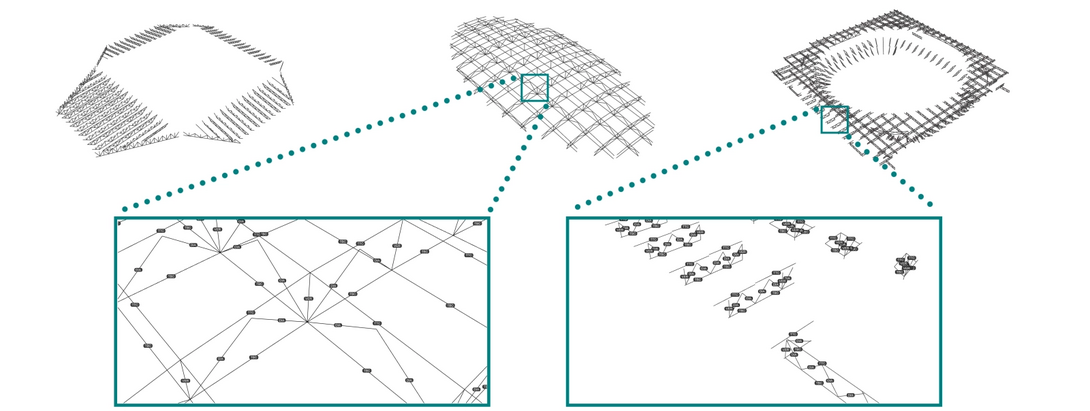

Through a project called “Intelligent Placeholders,” Friedman and his team are addressing the difficulty of obtaining accurate quantity and sustainability information early in a design process. As models are developed, Intelligent Placeholders uses AI to approximate the spacing and sizing of framing in structural bays that have not yet been fully designed. This allows the structural engineering team to identify and quantify carbon hotspots long before a design is finalized.

In another project, Friedman’s team uses generative adversarial networks (GANs) — machine-learning models in which competing neural networks use existing data to iteratively generate, test and improve new, realistic synthetic data — to rapidly lay out shear wall locations.

In this case, the team assembled a series of images identifying engineers’ preferred locations for shear walls based on a collection of past projects, then used those images to train a GAN. The resulting tool is an app that replaces the usual weeks of back-and-forth bilateral analysis between engineers and architects. In meetings with architects, Walter P Moore’s structural engineers can use the AI-driven app to quickly explore viable options for shear wall layouts.

![Shear wall GIF [animated]: GAN-generated shear wall designs in plan (courtesy of Jared Friedman) shear walls jared friedman](/sites/default/files/2025-02/shear%20walls.gif)

Additionally, Friedman and his colleagues are using graph neural networks (GNNs) to predictively auto-label structural elements of digital models. GNNs are deep-learning models that draw inferences from graphical datasets. In this project, GNNs are used to predict and check asset labels of model elements in order to better inform downstream analysis and detailing. Correctly differentiating whether a particular framing element behaves as a truss, beam or brace is critical for obtaining reliable results from structural analysis models. This labeling is another example of a process that, having once taken designers tedious hours to complete by hand, can now be achieved nearly automatically.

Obstacles to Wider Use

All three of these initiatives are made possible by huge datasets that Walter P Moore has slowly collected from its own design projects. It is among the high-volume firms with enough data to build models at scale — but even they find the process slow.

And retroactively collecting building data in a consistent format is difficult: even slight differences among BIM datasets’ file types, project conventions or software versions can prevent the kind of enormous-scale model creation happening with commercially available large language models (LLMs), which are trained on vast swaths of publicly accessible text. The building industry doesn’t have huge bodies of good, consistent, public data available to it, and this lack of consistency in data schemas prevents tools like the ones piloted by Friedman’s team from becoming widely available.

Friedman notes another obstacle, particularly salient in his focus area of embodied carbon and sustainability: “Even firms that have good embodied-carbon data don’t have enough incentive or standardized ways of sharing it,” he says.

He sees promise in industry-wide initiatives like SE 2050, a collaboration among large structural engineering firms that both incentivizes sharing project data and requires sharing of methodology. (View Walter P Moore’s most recent Embodied Carbon Action Plan, an example of the reporting required of signatory firms.) The architecture and mechanical, electrical and plumbing (MEP) engineering disciplines each have an initiative similar to SE 2050. Through these collaborations, AI will be able to leverage larger datasets to train models that can better account for sustainable design decisions from project conception through completion.

What Next?

Like others, Friedman appreciates AI’s ability to automate some of designers’ most mundane, tedious tasks. He notes, then, that architects in an AI landscape need to continue growing their ability and inclination to think systematically. Architects, he says, “should be knowledgeable evaluators of AI-generated results” — the agents accountable for excellent quality and the intangibles of design.

The landscape shifts constantly, but Friedman is optimistic. “Be open-minded and ready to embrace change,” he says. “To stay competitive in this profession will require integrating AI tools seamlessly into your design process. Architects have always had to pivot to keep delivering value in the wake of new technology; we’re ready for this.”

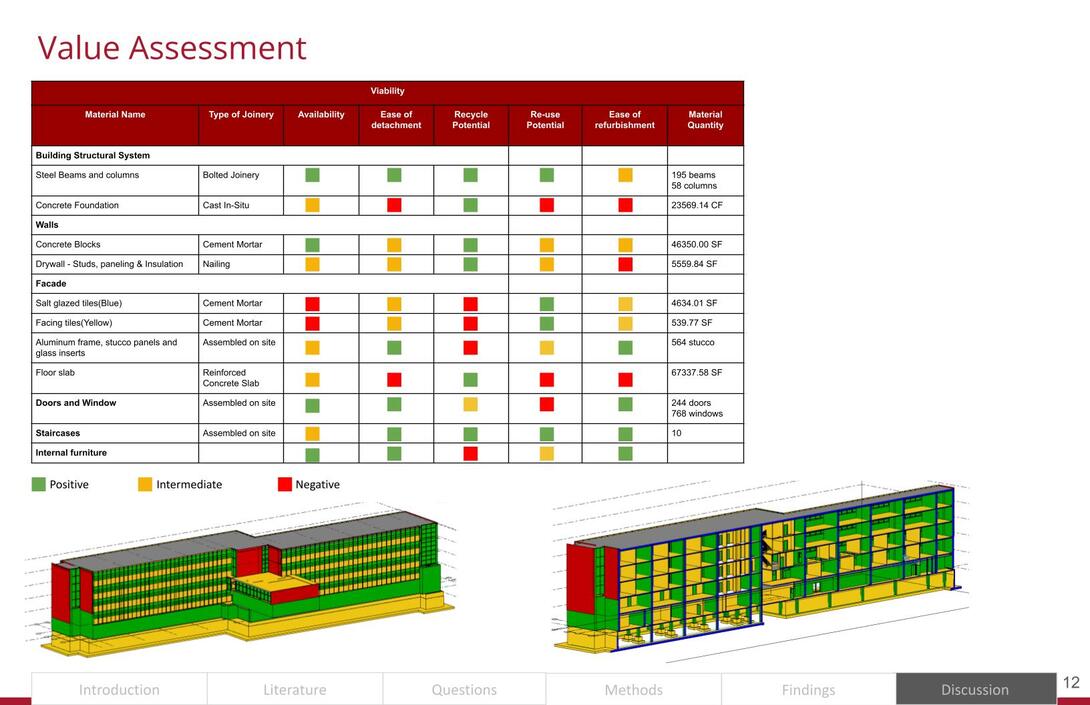

Tannaz Afshar (PhD-AECM ’26) is working on her dissertation: a project that will leverage Building Information Modeling (BIM) to assess and optimize material reuse in campus buildings, with the potential to build more sustainable construction practices at CMU and elsewhere.

"A BIM-Based Framework for Deconstruction and Material Reuse on a University Campus"

Abstract: The United States Environmental Protection Agency reports that over 600 million tons of construction and demolition (C&D) waste were generated in 2018, with demolition alone accounting for 94% of this total. While an estimated 90-95% of C&D waste could be recycled or reused, much of it still ends up in landfills. Deconstruction, which instead maximizes material recovery through the careful dismantling of buildings, offers a sustainable alternative by reducing waste and promoting circular economy principles.

Higher education institutions (HEIs) are increasingly recognizing their role in sustainability, as evidenced by the 348 institutions that hold a valid STARS rating. With extensive knowledge of ongoing and future construction projects, HEIs are well-positioned to lead in repurposing materials and improving campus waste management. However, there is limited research on how C&D waste management can be effectively applied in university settings.

My research focuses on closing this gap by developing a BIM-based tool to assess and optimize material reuse in campus buildings. Using Carnegie Mellon University (CMU) as a case study, I will employ a mixed-methods approach, including interviews with key stakeholders to identify challenges and opportunities in C&D waste management. A BIM-based simulation will then quantify and evaluate the reuse potential of salvaged materials. The final phase of the study will integrate this data into a user-friendly digital platform, providing stakeholders with insights on the triple bottom line — environmental, economic and social impacts — of material reuse.

By equipping policymakers and campus planners with actionable data, this research aims to support more sustainable construction practices, with the potential for integration into CMU’s master plan. Ultimately, this tool could serve as a model for HEIs and corporate campuses, fostering a circular economy and reducing the environmental impact of the built environment.

Design in Color: NOMA Pittsburgh Celebrates 10 Years

NOMA Pittsburgh celebrated its 10-year anniversary with the inaugural Design in Color party on Saturday, February 8. Along with the CMU College of Fine Arts and Carnegie Mellon University, Carnegie Mellon Architecture was a leading sponsor for the event. The celebratory evening included remarks from Carnegie Mellon Architecture head, Omar Khan, and awards to many who have been instrumental in the last 10 years of NOMA Pittsburgh, including our very own William J. Bates and Dr. Erica Cochran Hameen.

Enjoy these photographs from the gala, and spread the word: UDream applications are open for the 2025 cycle!

Celebrating the PJ Dick Innovation Fund Round One Awardees

On Friday, January 24, the Carnegie Mellon Architecture community gathered to celebrate the work of the inaugural year recipients of the PJ Dick Innovation Fund Faculty Grants Program. The first award cycle funded 10 research projects and six experimental courses that address the School's three pedagogical challenges: climate change, social justice and artificial intelligence. The showcase included everything from large-scale models, to books, videos and more. Faculty, staff, students, the PJ Dick team and friends of the School enjoyed snacks and conversation while learning about the impressive work that faculty recipients accomplished over the past year. The 2025 PJ Dick Innovation Fund awardees were also announced at the event.

We will cover some of the 2024 projects in depth in the next two editions of e-SPAN. Until then, you can learn more about the round one and two projects at the links below!

2025 PJ Dick Innovation Fund Faculty Grants Program Recipients

2024 PJ Dick Innovation Fund Projects

Alumni News & Updates

We invite all Carnegie Mellon Architecture alumni to keep us up to date on their awards, professional milestones and more. Send us your updates with a brief description and link to more information.

- Gregory Coni, AIA, CPHC (B.Arch ’15), Associate Project Architect at GBBN Architects, received the Young Architect Award from AIA Pennsylvania on December 3, 2024. The annual award is given to a Pennsylvania architect with less than 10 years from their date of licensure to recognize their exceptional achievements and future promise as well as to promote their continuing development. Coni was honored for his service to the profession and society through his work with the AIA Pittsburgh Young Architects Forum (YAF), ACE Mentor Program of Western PA, and Down Syndrome Association of Pittsburgh. Coni was also featured in a profile in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette highlighting his professional journey and contributions as an advocate to the Down Syndrome community.

- Jordan Luther, AIAS, Assoc. AIA, NOMA (M.Arch ’23), Vice Chair of the AIA Pittsburgh Young Architects Forum and President of the American Institute of Architecture Students, has joined the AIA National Board of Directors as 2025 Student Director.

- Chaz Barry, NOMA (M.Arch ’19), Architectural Associate at AE Works, has been named Secretary of NOMA Pittsburgh’s 2025-26 Executive Board. He joins a dedicated team of professionals ready to drive forward the organization’s mission of empowering and advancing Black architects and designers in the Pittsburgh community.

- Stephen Michael Wilder, NYCOBA-NOMA, AIA (M.S. in Architecture ’04), Principal Architect of Think Wilder Architecture, has been named President at nycoba | NOMA (NY Coalition of Black Architects | National Organization of Minority Architects - NY).

- Doors Unhinged, under the direction of CEO Andrew Ellsworth (B.Arch ’01), was selected as a Phase 2 winner in the Re-X Before Recycling Prize from the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) and American-Made Program. The prize money will be used to accelerate the rollout of the company’s refurbished and remanufactured door products and expand into the East Coast markets.