e-SPAN Newsletter v030: Towards a More Equitable Built Environment

Towards a More Equitable Built Environment

ARCHITECTURE X REVOLUTIONS X RESOLUTIONS

Students in the Common Imaginaries: Urban Playbook for Radical TypoMorphological Formations studio pose in Chiang Mai, Thailand. The studio is conducted by Tommy CheeMou Yang.

Dear Carnegie Mellon Architecture Community,

As we look forward to finishing out the semester with final reviews and exams on the horizon, I’m reflecting on the conclusion of our fall Public Programs series, Revolutions/Resolutions. Our last lecture in the fall series was conducted by 2023 AIA Topaz Medallion recipient Sharon Egretta Sutton, FAIA. Professor Sutton shared her long history of architectural teaching and community activism and described how to combine them in what she calls a “pedagogy of the commons.” As a school that has made social justice a key pedagogical objective across our programs, we were inspired by Professor Sutton’s presence and message.

In this e-SPAN newsletter we are highlighting two alumni, Ashley Archie (MUD ‘15) and Lizzie MacWillie (B.Arch ‘07), who are addressing social justice issues in the built environment. Their trajectory from their education in architecture to government and community work, respectively, is an important lesson in the value and contribution a design education can provide. The roles of policy, advocacy and activism cannot be underestimated in creating a more inclusive and equitable built environment. Community voices and government agencies can provide a critical counterweight to the increasing power of developers, builders and investors in dictating the design process.

We are also featuring in this issue a global studio, Common Imaginaries: Urban Playbook for Radical TypoMorphological Formations, being conducted by Tommy CheeMou Yang in Chiang Mai, Thailand. It is part of the school’s shifting focus to the global south and the ways architects will need to function as agents of the global majority. Working with government and community agencies is a critical part of this process, and developing new techniques to understand and communicate design intent is an important part of the studio. Additionally, we are introducing a series of courses under the title of New Pedagogies that will expose students to new design techniques and concepts that will help them better understand the global context and ways to act in it.

I appreciate the many ways that alumni and friends of Carnegie Mellon Architecture participate to build a unique community. Following Thanksgiving, I kindly ask you to consider making a gift to improve the experience of our students, faculty, staff and alumni in architecture. The School of Architecture Head's Innovation Fund enables me to direct funds flexibly and thoughtfully to help us meet students’ needs for materials for coursework to create equity in the classroom; tools to perform cutting-edge research projects; and travel funds to locations far and wide to ensure opportunities for all who want to study overseas. These are just a few examples of how your support will enhance opportunities for the next generation of architects. Please visit our giving site on or before Tuesday, November 28, 2023 to participate.

As ever, we’re so grateful for your engagement with the school, and we wish you and yours a joyful holiday.

Omar Khan

Head of School

Built Environment Diplomacy: Ashley Archie (MUD '15)

Ashley Archie (MUD ‘15) is always building and rebuilding: building global connections, cities and teams of problem solvers. A partnerships officer in the US Department of State’s (DOS) Office of Global Partnerships since 2021, Archie forges collaborations among the federal government and the private sector to advance foreign policy priorities like global health, sustainability and emerging technologies.

And she’s quick to point out that “the private sector” is not synonymous with “large corporations.” When asked about partners, she rattles off an eclectic list of entities: universities, small- and medium-sized enterprises, corporations, think tanks, faith-based organizations and foundations.

Her team, she says, is eager to think broadly and collaborate with groups that share the same goals and priorities as the DOS and “can help the Department of State creatively push the needle on foreign policy.” To achieve that goal, the Office of Global Partnerships uses various tools for engagement, such as Partnership Opportunity Delegations (PODs), to find bright, creative, talented people and organizations, and to identify areas where their priorities overlap with the DOS’s work.

The team casts a wide net, says Archie, reaching out to affiliation organizations with large membership bases, offering open-call grants and convening roundtable problem-solving sessions. “We bring together smart people from across the private and public sectors, put them in a room together, and develop creative solutions.”

At the moment, a large portion of Archie’s work relates to sustainable reconstruction efforts in Ukraine.

“The Ukrainian people and their leaders—amidst all that they’re experiencing—are beginning the long and complicated process of rebuilding their cities. I commend them for already thinking about rebuilding in a way that’s environmentally sustainable and good for all Ukrainian people.”

As an architect and urban planner, Archie views diplomacy through the lens of the built environment, and vice versa. “With their large infrastructure and major energy consumption, cities will be the sites of a huge amount of recovery in Ukraine. My team’s job—our privilege—is to facilitate the exchange of knowledge and ideas so that the Ukrainian people can make the best-informed decisions about how they want to redesign and redevelop their cities. We get to position the right people to be part of these conversations.”

As a part of the Ukraine Partnership Series, Archie is doing just that. The Ukraine Partnership Series serves as a platform to discuss opportunities for investing in Ukraine’s short- and long-term recovery. Through a collaboration with a NGO, the DOS is supporting a Ukrainian delegation of government officials and design and construction experts to visit the San Francisco Bay Area to meet with leading researchers, technologists and process experts to facilitate an exchange of ideas and expertise that will pave the way for reconstruction success. This trip will demonstrate new ideas and offer opportunities for Ukrainians to share their knowledge with communities throughout the nation.

These conversations, Archie stresses, are not focused exclusively on Ukraine’s largest or most renowned cities, which receive the most international attention. In fact, the DOS is thinking creatively about how to help support the people who, in rebuilding efforts, traditionally receive the fewest resources. Through its Diplomacy Lab program, which partners DOS offices and bureaus with universities for ad hoc research projects, the DOS is currently working with multiple universities to devise ways to empower and support small Ukrainian cities in redesigning and rebuilding sustainably.

As “both a human and an architect,” Archie has always felt called to be of service to her local and global communities.

These core values have guided a career trajectory dotted with creative turns.

In Carnegie Mellon Architecture’s Master of Urban Design (MUD) program, she was particularly drawn to learn tactics of community engagement and collaboration. She put these into practice through work in multiple traditional firms and solo consulting before making a leap into the Peace Corps, with whom she served as a community development volunteer in Kosovo.

“From the outside, that move may seem odd,” she laughs, “but I was exposed to the Peace Corps during undergrad, and—given its alignment with my values—for me, joining the Peace Corps was inevitable.”

Ashley Archie (middle) poses with students at a speaking engagement in Kosovo. Image courtesy of Ashley Archie.

Her work in Kosovo, helping communities reimagine and redevelop their neighborhoods, brought together all of what she loves best about architecture: community engagement and collaboration, service through the built environment, and an international lens. After completing her Peace Corps term, she asked an embassy contact to keep her in mind for any future government work in foreign policy. He forwarded her resume to the DOS, which recruited her for the Office of Global Partnerships.

To architecture students with a desire to serve their communities, Archie recommends a flexible career mindset and the willingness to pursue a variety of opportunities to “take in and give out.”

“I’ve allowed myself to dabble, to gain many forms of experience that have brought me here,” she says. “Traditional practice, independent consulting, the Peace Corps: everything I’ve done has worked together to put me right here, where I need to be.”

A Radical Imagination: Lizzie MacWillie (B.Arch ‘07)

According to Lizzie MacWillie, a radical architectural imagination is possible—and necessary—everywhere. MacWillie (B.Arch ‘07) has worked for a major global architecture firm, directed an office for a small and agile community-design practice, and is now Assistant Director of the J. Max Bond Center for Urban Futures at the City College of New York.

With this varied experience, MacWillie insists that everyone, “not only those working at a community design center,” has a role in work for social justice. “The ways that architects and designers can show up for justice work are innumerable, both through our paid work and through our agency as individuals with knowledge, skills and training about policy and the built environment.”

Near the end of a writing and editing stint at OMA, MacWillie found herself at an impasse. On the one hand, she had met amazing colleagues and learned a great deal working for a firm with a giant global presence. On the other hand, she was appalled by OMA’s labor practices and the misalignment of some of its projects with her personal and political values. “I found myself asking, ‘what would I need to stay at a place like this?’” she remembers. “What would I do if asked to work on something that didn’t align with what I thought was right?”

She made the decision to leave OMA and join buildingcommunityWORKSHOP ([bc]), based in Dallas.

“I haven’t found such a thing as a perfect practice, where I’d never have ethical questions about fit, clients or funding,” she notes. “But at [bc] we had those conversations often and openly. I feel lucky to have been part of a practice where that sincere reflection was possible.”

MacWillie encourages all justice-minded students and architects to “try to find a place where you can bring your full self to your work. Even in progressive firms, I’ve had to practice voicing my thoughts and opinions. It’s been a skill highly worth learning, worth putting time and effort into. And if you're in a situation where that feels untenable, recognize it's not worth your mental health to stay at a place where you're being treated poorly for standing up for what's right.”

As the director of [bc]’s Dallas office, which also operated offices in Houston and Brownsville, MacWillie worked across multiple community-design projects whose success, the firm says, depends on “reaching those residents not typically sought out by the design and planning community.”

MacWillie is clear-eyed about the source of this omission: “A deep root of racism, historic and present, manifests itself throughout the built environment, in inadequate housing, communities divided by highways, and environmental injustice. These are the long-lasting effects of redlining and urban renewal—policies put in place generations ago that continue to have detrimental effects on communities and individuals—and current day racist zoning, lending and other practices.”

With her [bc] team and community members, MacWillie sought to redress these effects in ways both creative and interconnected.

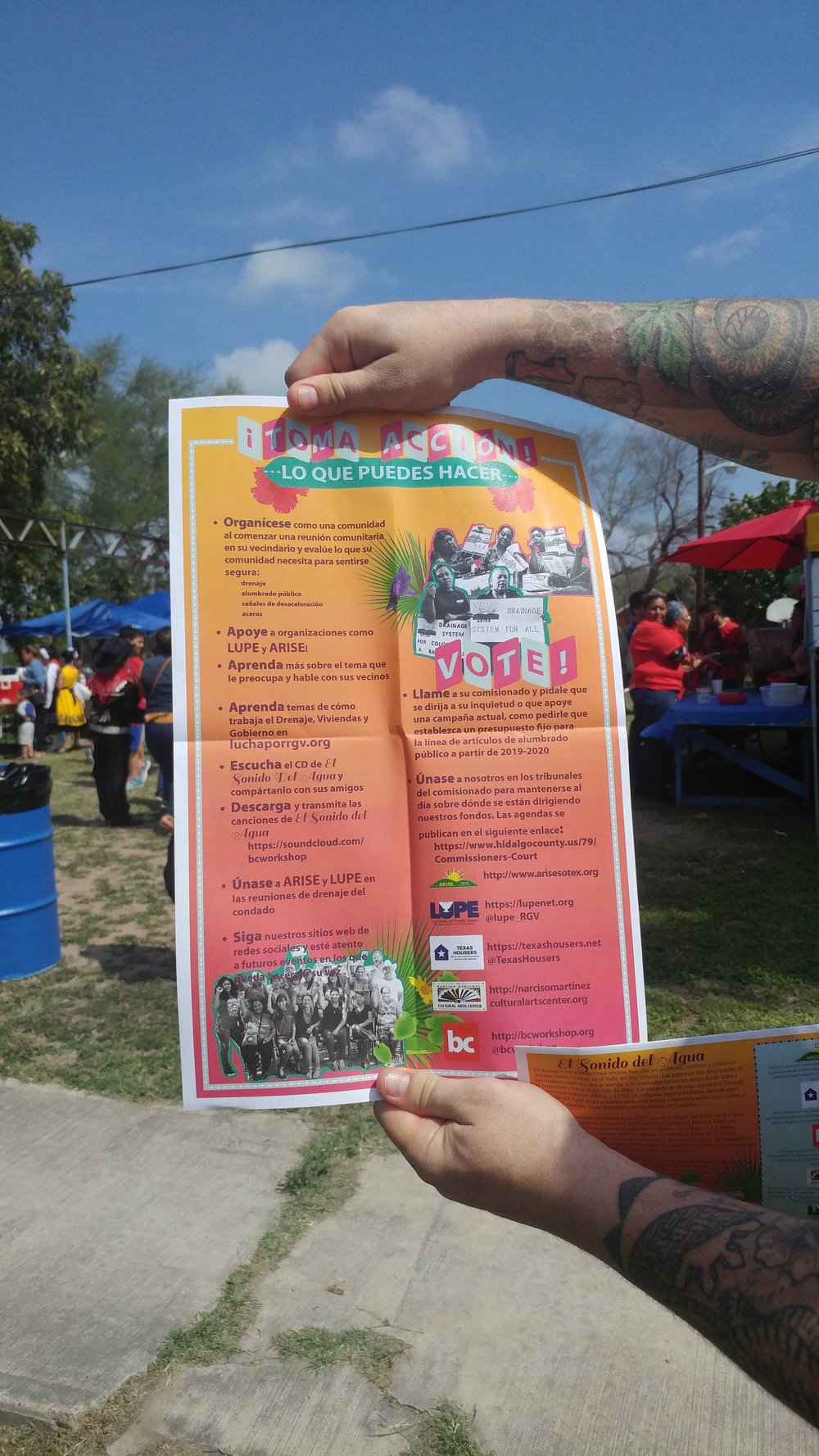

One project, El Sonido del Agua, highlights the power of narrative, art and place-making/place-keeping as creative processes capable of facilitating real change.

In collaboration with [bc] and residents of the Lower Rio Grande Valley’s colonias (unincorporated communities with historically inadequate access to municipal infrastructure), local musicians released an album of songs about residents’ experience of flooding in their communities. That album became part of a successful campaign to improve stormwater drainage, with songs performed in venues as varied as community events and the commissioners’ court.

To MacWillie, El Sonido del Agua emphasized not only the well-understood importance of collaboration with residents and community groups, but also the “many different ways there are to practice architecture, and designers’ capacity to imagine new futures where equity is centered.”

MacWillie acknowledges that it can be much easier to exercise this imagination within academia than in daily practice. She stresses the importance of leaning on others to feed one’s imagination for what’s possible. “Find people in your firm who are willing to think creatively with you about ways to center the experiences of people who have historically been marginalized. Join organizations like the Architecture Lobby or the Design Justice Network. Keep up with people like Cruz García and Nathalie Frankowski (former Ann Kalla Visiting Professors), who can inspire new thinking.”

Social justice may not top every firm’s priority list, but MacWillie insists that equity-centered work is possible and in need of support everywhere.

“There’s not a lot of money in radical imagination, in imagining a world that’s anticapitalist, that centers the perspectives of women and Black/Indigenous people of color,” she notes. “But wherever you’re able to bring that imagination to a more traditional practice, do. And at the same time, look to build ways to earn a livelihood from imaginative, collaborative justice work. That’s the goal.”

Common Imaginaries Studio Travels to Chiang Mai, Thailand

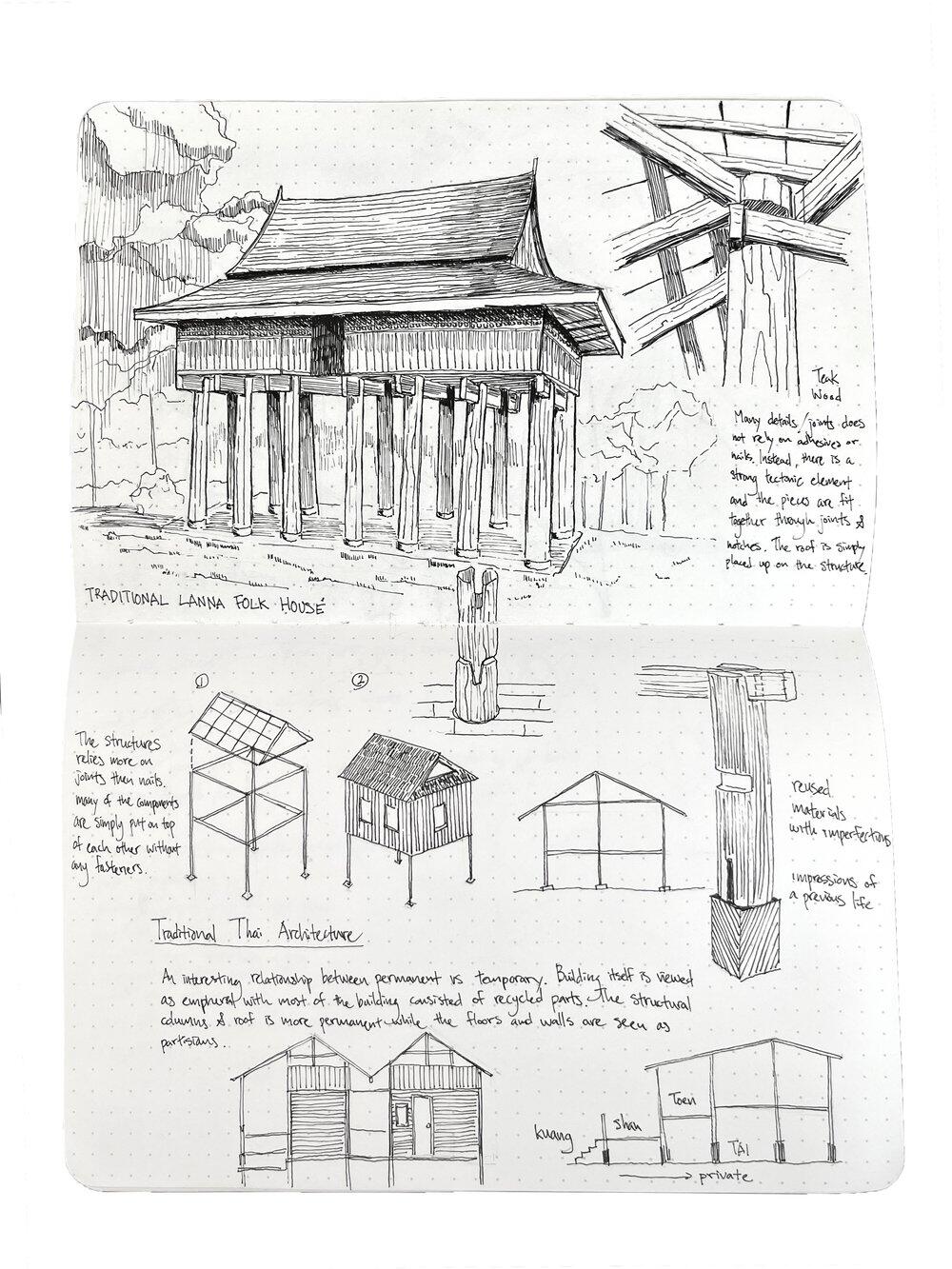

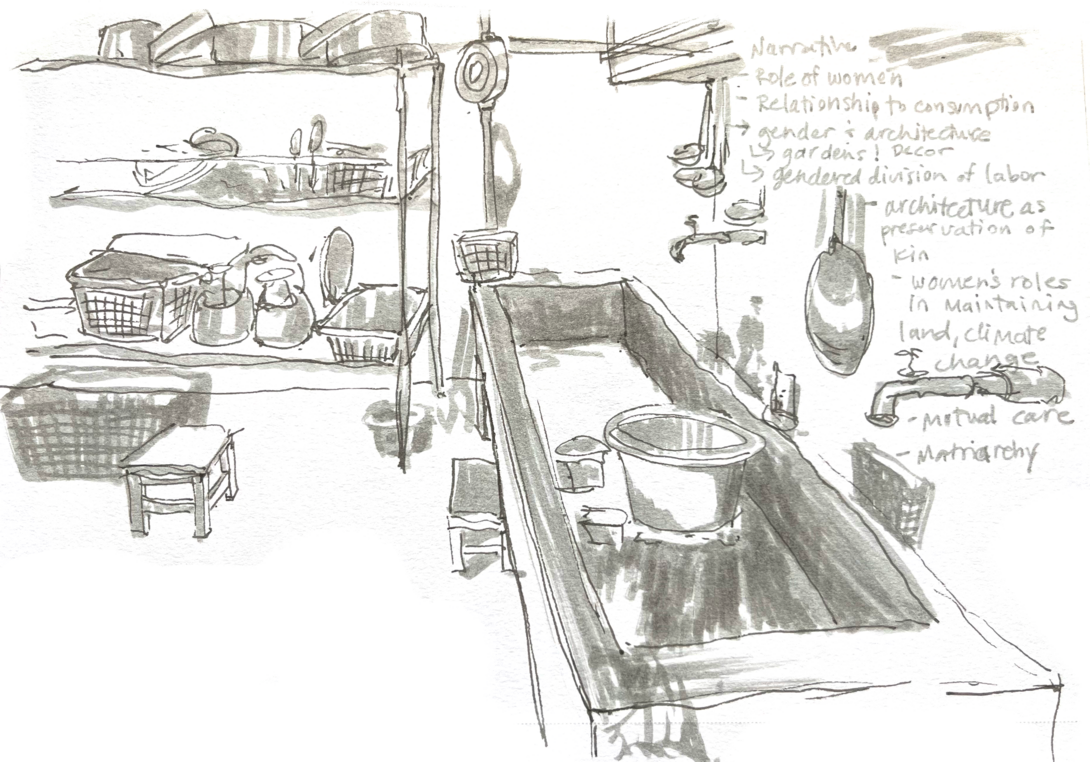

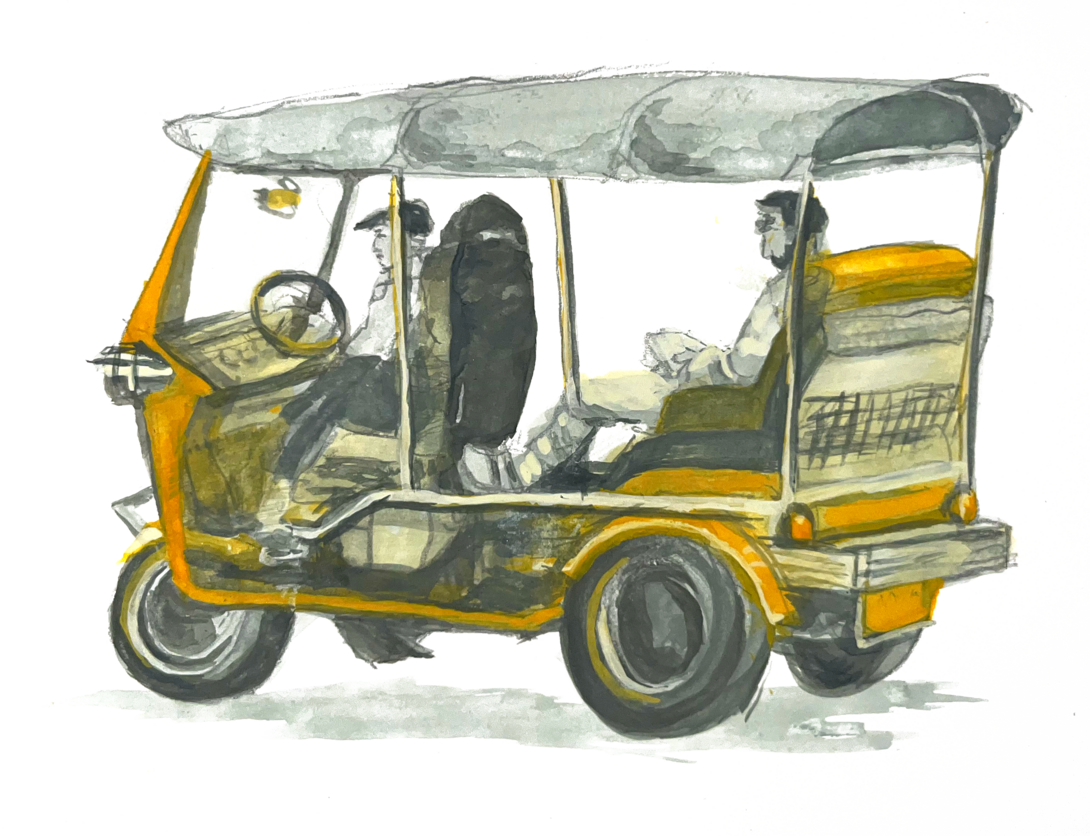

Students in Tommy CheeMou Yang’s Common Imaginaries studio (mentioned in September’s e-SPAN issue) traveled to Chiang Mai, Thailand in August to explore community-empowered architectural design and activism and how “contemporary building practices can be recalibrated with the embodied knowledge of everyday stewards.”

Students sketched the various architectural landmarks they encoun

tered; see some of their drawings below. Learn more about the studio and read about student Andy Jiang’s SURF-funded archive project.

All images courtesy of Tommy CheeMou Yang.

Lanna Architecture Center, sketch by Brian Hartman.

Image

| Image

|

Image

| Image

|

Clockwise from top left: Lanna Architecture, sketch by Jerry Zhang; Grandma Anporn’s House, sketch by Anna Soryal; TukTuk Painting; sketch by Anna Soryal; One Nimman, sketch by Anishwar Tirupathur.

Students with Anjarn Junlaporn at Northforest Studio.

Learn more about the Common Imaginaries Studio >>

Spring ‘24 Course Highlights: New Pedagogies

New for the spring semester, the New Pedagogies courses address our three pedagogical challenges: climate change, artificial intelligence and social justice. These courses will introduce students to topics in architectural theory, design and technology; broaden students' perspectives; and experiment with new teaching techniques that expand the school’s repertoire of pedagogical approaches.

Image

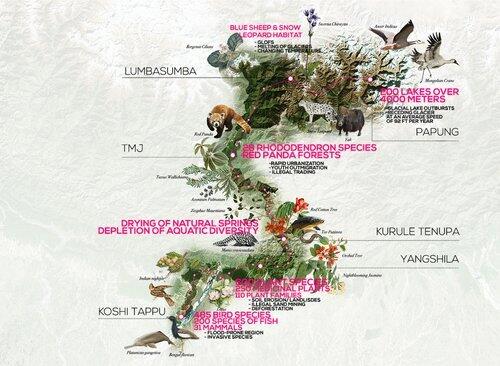

| Co-Designing Vertical University’s Living Classroom in Kurule This seminar emerges from the instructor's work co-founding the "Vertical University" project in Nepal. As a subversion to the traditional way that we understand knowledge, the "Vertical University" builds on the learning potential inherent in the place-based, deep-seated indigenous knowledge of farmers living in biodiversity-rich landscapes. The project spans across a vertical elevation from Koshi Tappu (67 meters) to Mount Kanchenjunga (8,586 meters), the third tallest peak in the world.

|

Material Regeneration The energy crisis and climate change have impelled architects to challenge many standing assumptions in material culture and rethink the relationship between materials, the environment, construction methods and labor. This seminar offers a critical view of conventional material systems and practices and examines ways to shift towards adoption of materials that are carbon-neutral and regenerative, and those made from waste. | Image

|

Image

| A Multiple-Making Approach to Inquiry in Craft + Computation This course uses ethnographic methods, computational modes of inquiry, and design to study manual craft and its intersections with technological practices. By re-describing, representing, and re-interpreting craft practices in multiple ways, we will consider ways of repairing both. Advocating for exploratory, experimental and improvisational processes, the course seeks to situate craft as a site and method for critical, poetic and speculative thinking that imaginatively and materially reconfigures theory, practice and pedagogy. |

Unsettling Ground: Retiring the God View. Through the filmic medium, students will practice “cinematic cartography” as a geospatial means to unearth the hidden logics that delimit spatial futures as a consequence of cartographic maps, to move toward deriving expansive ways of seeing and doing that offer new space-time possibilities. Through a series of lectures as guiding tutorials, and key reference materials, students will each produce a filmic offering and a group lexicon which will be presented though a Film Exhibition and Seminar at the end of the semester. | Image

|

Alumni News & Updates

To have your alumni news featured, please email Kristen Frambes at kframbes@andrew.cmu.edu with a brief description and link to more information.

Gary Li AIA, LEED Green Associate, NCARB (B.Arch ‘17) has been named a Principal by Kostow Greenwood Architects (KGA). Li, promoted to Principal from Associate Architect, joined KGA in 2017. He joins Founding Principal Michael Kostow, and new Principal Lena Dau-Ping Fan, as equity partners.